Dear Joe,

Have you heard about or seen C.D. Wright's new and last book? It's called Casting Deep Shade, and it's about, or circles around, beech trees. Yesterday (though now, sending out this letter, it's several days back) I made my way through the aftermath of a snow storm here in Seattle and took a streetcar up to Elliott Bay Book Company, an incredible bookstore here, to buy it. I first heard about Wright's book when I visited Copper Canyon Press in Port Townsend last September—Andrew and I drove up the Olympic Peninsula with my friend Anneka, whom I know I've told you about, and I went for a walk with Michael, one of the editors of the press, in Fort Worden, the amazing park in which Copper Canyon and whole host of other art organizations are headquartered. As I was getting a tour of the offices at the end of my visit, Michael introduced me to a young woman who lived in Port Townsend, and who had worked with Wright on the project—and, by the kind of happenstance that is also a product of being in a small world, in a way that's both delightful and a bit frightening, this woman, Rowan, was someone Anneka knew from living in New Orleans, and who I'd even heard about from another friend.

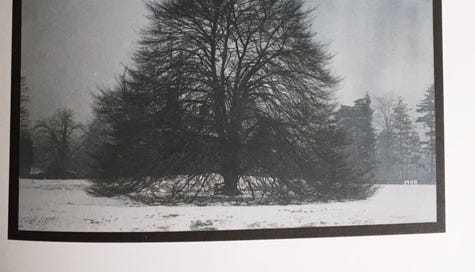

What I learned about Wright's book during that conversation piqued my interest, and I got even more excited about it a few weeks back, when I heard more about what it was like as a physical object. It's got what I want to refer to as a triptych cover—there are two hardcover flaps that fold out from a text block—and Wright's words, mostly lineated like prose, are strewn also with images: archival illustrations, photos Wright took of trees, pictures of Wright herself (there is a way in which this book seems to be, as my cousin Ben writes in the foreword, “both C.D.'s book and a loving tribute to her”), and these amazing photos by Denny Moers, with whom Wright collaborated on several other projects. And it's focused on trees! This was (perhaps obviously) a huge part of my excitement about the book, and the main reason why, despite feeling that I really shouldn't at the moment, buy another thing to read, particularly a $35 hardcover, I went and bought it anyway. I'm drawn both to the idea of a poet's book about trees, and to trees themselves!

Embarrassing but true: when I was in high school, in a period that coincided with my listening to a ton of emo music and reading lots of 19th century Russian literature, I decided (and declaimed, but only to myself) that “nothing was more beautiful” than a winter tree silhouetted against the sky. My favorite tree in Santa Fe was on Pacheco Street, conveniently also the street on which my crush Matt S—— lived, and I took pictures of the tree in four different sorts of light and hung the photos on my bedroom wall. In college, when I studied Moby-Dick with my much-beloved, much-mentioned teacher Geoff Sanborn (the same teacher I worked with at Amherst College while we were at UMass), Geoff clarified that appreciation a bit, or gave me language for it. He talked about his love (and Melville's love!) for trees as living presences that remind us of something important in our nature, and in life's own tendencies; they are, like so much else in Melville's work (and I've written of this a bit already in a previous Ear Mountain), manifestations of an upward-tending influence, both literal and metaphorical. I'm looking right now at an essay Geoff wrote about “Melville and the Nonhuman World,” in which he (Geoff) writes that “Melville represents trees in a way that makes it possible to imagine that they too have nobly resistant spirits, opening responsively and expressively onto the world.” The essay begins with a recounting of a visit this writer named Maunsell B. Field made to Arrowhead, Melville's house in Pittsfield, where Field and his companion Felix O.C. Darley (don't their names sound made up?), as Field remembers it, “found Melville, whom I had always known as the most silent man of my acquaintance, sitting on the porch in front of his door. He took us to a particular spot on his place to show us some superb trees. He told me that he spent much time there patting them upon the back.” Geoff then goes on to say:

What Field is most struck by in Melville's remark about his trees is that he speaks of “patting them upon the back”—that he not only perceives the trees as beings like himself, with nobly vertical spines, but is moved to socialize with them. Although the nature of that socialization is, in Field's anecdote, unclear, the evidence of Melville's work suggests (as I will show) that it involves both receiving inspiration from the trees and conveying friendly, admiring feelings to them… [In human and nonhuman encounters alike], the value of the interaction is dependent on a mutual summoning of the kind that occurs when, in the first sentence of the first chapter of Moby-Dick, our narrator-to-be says, “Call me Ishmael.”

This description of a “a mutual summoning” is very exciting to me, in part because it feels like a way of describing a kind of attentiveness to the world that both acknowledges and increases its aliveness. There's a Frank O'Hara quote I really love (which I believe I discovered in David Shields's Reality Hunger, which I really hate—but it gave me the quote, so I guess it's good for something): “Attention equals life, or is its only evidence.” Something about Melville's engagement with his trees reminds me a lot of what O'Hara's saying there, in part because Melville's attention feels like a way of acknowledging nonhuman life as both equally as vital and vigorous as his own and as something which, once acknowledged, expands one's own vitality.

Here's where, finally, I leap back to C.D. Wright's book! I'm still just at the start of it, perhaps a third of the way through, so maybe what I'm about to say will be proven wrong—but one of the things I've been excited about thus far is that Wright makes no explanation of what drew her to beech trees, why she's writing about them in particular. The project is subtitled “An Amble Inscribed to Beech Trees & Co.,” and it simply begins—the book opens—with a list of some qualities of beech trees, and from there it roams. It circles around poetry, and history, and science, and Wright's own early life, and travels all around, with Wright looking, wherever her gaze goes, somehow towards or into trees. It's as if by finding an interest, or allowing it to stretch its limbs, she's also found a form that allows her to pay attention to anything and everything. The sight of the beech starts the amble, but that is only the start.

Sometimes I feel like this is what all writers, or at least a lot of my favorites, are looking for—some spark, some structure that will allow them to funnel everything into their work. Moby-Dick operates in the same way, I think. Ways of writing like that, or of bringing that quality of omnivorous attention into one's day—that's about as close as I come in my own mind to believing in a religious practice, some system of faith from which to derive both meaning and joy. My dear friend Pam, who was also my colleague at the Care Center, said this amazing thing once about education, and I think about it often. She said that ultimately the question that learners—people who have really “bought in” to education—are always asking, and what education is always trying to answer, might be the question “How do I not waste my day?” When I write that down (without Pam's lovely inflection), it maybe sounds negative, but to me it's actually a positive question, and does kind of feel like the question, in that it is always one to be asking oneself, and also insofar as you can think of it both in terms of what you owe to yourself and what you owe to the ever-expanding and ever-encircling layers of community and others around you. I can't help, as I write this, also thinking of DFW's “This Is Water” speech, which is of course also about this aspect of education—education as giving a learner choice about what she pays attention to. One way of not wasting your day, it seems to me, is to follow an interest, any interest, and see how inevitably and inexhaustibly curiosity leads elsewhere, keeps going. So that C.D. Wright can write in her work “about” beeches:

To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul. Simone Weil, continuing: A human being has roots by virtue of his real, active, and natural participation in the life of a community, which preserves in living shape certain particular treasures of the past and certain particular expectations for the future.

And Melville can write in his book “about” whales:

One often hears of writers that rise and swell with their subject, though it may seem but an ordinary one. How, then, with me, writing of this Leviathan? Unconsciously my chirography expands into placard capitals. Give me a condor's quill! Give me Vesuvius' crater for an inkstand! Friends, hold my arms! For in the mere act of penning my thoughts of this Leviathan, they weary me, and make me faint with their outreaching comprehensiveness of sweep, as if to include the whole circle of the sciences, and all the generations of whales, and men, and mastodons, past, present, and to come, with all the revolving panoramas of empire on earth, and throughout the whole universe, not excluding its suburbs. Such, and so magnifying, is the virtue of a large and liberal theme.

(I just read that second quote out loud to Andrew and laughed. I love “Friends, hold my arms!” I actually just love the whole thing.)

The commonality between these two passages is that both of them, and both of the projects from which they're excerpted, expand way, way beyond the ostensible bounds of their respective subjects. Pay attention to something and it becomes a way of paying attention to everything. Roots are a metaphor, the whale's largeness is a metaphor—and through the leaping alongsideness of figurative language, and of thinking itself, each book lets us engage with a wide swath of world.

That's one of the pleasures of reading this kind of work; another is that reading it simply seems to help me see more. Last night I was reading the C.D. Wright book, occasionally exclaiming over the pictures of trees, and I looked up as I stood to get ready for bed and saw the tree in our neighbor's yard, set black against the strange pale glow of the snow coming down again here, rare and illuminated. I've lived in this house for a full two months, spend most of my time in this living room looking out the window, and yet I don't think I've ever fully seen, which is to say noticed, that tree. I was amazed at how beautiful it was and also amazed by how reading showed it to me. Books are old technology, but what they do seems revolutionary still, and never stops surprising me. And it's also why they never feel very separate for me, in why I love them, from why I love conversation. Both remind you of what others see, and when you listen to that you can start seeing it too. (My cousin Matt, picking us up to go cross-country skiing the other day, said, as he looped around the roundabout at the end of our block, “Wow! What a great street tree!” I had never taken notice of that one, either; now I see it every day.)

I also recently read, because my dear friend Molly sent me an advance copy taken from the bookstore at which she works, Ross Gay's new book The Book of Delights. In the preface, which is short but which I'm about to quote almost in full, Gay shares the premises under which he wrote the book:

One day last July, feeling delighted and compelled to both wonder about and share that delight, I decided that it might feel nice, even useful, to write a daily essay about something delightful. I remember laughing to myself for how obvious it was. I could call it something like The Book of Delights.

I came up with a handful of rules: write a delight every day for a year; begin and end on my birthday, August 1; draft them quickly; and write them by hand. The rules made it a discipline for me. A practice. Spend time thinking and writing about delight every day...

It didn't take me long to learn that the discipline or practice of writing these essays occasioned a kind of delight radar. Or maybe it was more like the development of a delight muscle. Something that implies that the more you study delight, the more delight there is to study. A month or two into this project delights were calling to me: Write about me! Write about me! Because it is rude not to acknowledge your delights, I'd tell them that though they might not become essayettes, they were still important, and I was grateful to them. Which is to say, I felt my life to be more full of delight. Not without sorrow or fear or pain or loss. But more full of delight. I also learned this year that my delight grows—much like love and joy—when I share it.

In a way, what Gay decided to do is the opposite of Wright's project: he created a form that had nothing to do with any one concrete subject, a structure that allowed him to select absolutely anything to write about, provided it made him happy. He's casting wide, and Wright, to use 2/3 of her title to describe her project, is casting deep. But the effect, for the reader, is essentially the same. Both books are the legacies of a “discipline” of attention. And that allows for a finite work to feel also encyclopedic and extravagant in the most exciting way, full of both the variousness of the writer's mind (a pleasure, a delight always, to remember that others' brains are impossibly various!) and of the wild heterogeneity of the world itself. Wright on her outfit:

I sit here eating “carefully watched over” cashews grown in India, from one of the 102 billion plastic bags used annually in the US, wearing a linen shirt (albeit secondhand) made in China, jeans fabriqué en Haïti, Delta Blues Museum T-shirt made in Honduras… a walking, talking profligate.

Gay—just after he's mentioned that during the composition of this particular delight he's reading “C.D. Wright's last book, The Poet, the Lion, Talking Pictures, El Farolito, a Wedding in St. Roch, the Big Box Store, the Warp in the Mirror, Spring, Midnights, Fire & All, which I love and mourn its being the last one, forever the last one”—but Ross, future delight, there is another one coming!—anyway, Gay:

Do you ever think of yourself, late to your meeting or peed your pants some or sent the private email to the group or burned the soup or ordered your cortado with your fly down or snot on your face or opened your umbrella in the bakery, as the cutest little thing?

(It's hard, writing this to you, not to want to go even more quote-crazy than I already am, because both these books are just so good. And there's all sorts of cross-pollination—the pawpaw, to let me have just one more example. Wright: “I know I ate of the pawpaw one time only. I remember a cross-between-an-apple-and-banana flavor with the more-banana-than-apple texture.” Gay: “It tastes like a blend of banana and mango, in that tropical ballpark, shocking here in the Midwest...”)

Reading about other people's curiosities or joys are, as Gay describes his own attentiveness as being in his preface, infectious. Delight breeds delight, and witnessing attention, whether a sober sustained kind of looking or the brief flares of excitement in Gay's essayettes, breeds that kind of care-within-encounter in the reader, too. This is, in the end, how we don't waste our days, I think: we give them and the living beings in them our regard and enthusiasm and inquisitive energy. And they in turn give us more—more of what? I'm not sure—but more!—in return. Towards the end of Geoff's essay on Melville and the nonhuman, he writes, thinking again about trees:

Subject to “the same all-stiffening influence” that we are, groaning in their trunks in response to it, but nevertheless rising, spreading, and holding their ground, and doing so on a larger scale and for a longer time than just about any other organism on the planet, trees are, like whales, godlike in the best sense: superior enough to awe and yet comparable enough to give joy.

I love that! And I also think that I could add to that category books themselves, or their writers' consciousnesses as filtered through the text: they too are “superior enough to awe and yet comparable enough to give joy.” (Wright talks in Casting Deep Shade about how the origins of the word “beech” and “book” are in many languages the same. And of course those godlike trees are literally what makes up the bound pages I am always clutching to myself and talking about wildly…) I feel infected in the best way by books, and also feel a funny impulse, with both the Gay and the Wright books (great homophonic names there), to give them away, so as to further their contagiousness. The whole time I've had the C.D. Wright book, I've been tormented/thrilled by a feeling that I should definitely give my copy to Anneka, who would love it, I think, being, as she is, a former arboretum employee (alongside our friend Bill), and a fan of both research and poetry. I've also really wished I could send it along to you, in large part because I've thought many times while reading it about your presentation in Dara's class on the use of images in text—and these spectacular pictures of trees, as well as the overall timbre of the book and its topics, has me wanting to know what you'd think of it. And Noy and Sam would like it too, and Matt and Gwyneth, and Molly… and my friend Paul would love the Ross Gay book… and so on and so on. Maybe someday I'll become wealthy and will shower people with too many books. But for now I'll settle on this letter, and its crazy hodgepodge of enthusiasms.

I want to say before I end this, Joe, that I always have different worries about each Ear Mountain, and my worry about this one is that won't feel personal, that it is not enough of a tribute to you and all the things that are great about you! I think implicit but not yet said in my choosing to send this your way is that you are someone who has always struck me as sharply attuned to the world, and to the nonhuman world in particular, and that attention comes out so beautifully in your poetry. So I write this to you as I see you in that way, as a cousin of Wright and Gay and Melville and the way each of them sees both clearly and feelingly, to take that latter from (as my Youtube yoga video instructor of choice always says) “Mr. Shakespeare.” But also, as I have written here before, there are a half-dozen shadow Ear Mountains for every one I send out, and one other, for you, begins where I will end with you here: in our poetry class. I've told this story several times to other friends as an example of one of my favorite things about the world. Sitting around the long table in Dara's house on the first day of class, or sitting in a group of people anywhere, invisible—yes, delights—are present: you never know who might be your future friend, whose seeing might shape yours. I sure am glad that I was in that room and you were too. And now my next hope is that we can look at some trees and/or talk about some books in some other room or on some new walk sometime soon. McCall? Seattle? Just let me know and I'm there.

your pal,

Liza

Thank you all for reading Ear Mountain, if you are reading it! Starting now, I'm going to be sending these out every other Sunday—I need a little more time between each one, both because I've been writing too slowly and because I've been writing too quickly, if that makes sense. I also want to write some fiction and need more time for that. Look for the next installment on the 24th. And also this one is a day late, whoops! Better late than never.