Dear Molly,

Though we are more than a month past Midwinter Day, and also well past your amazing read-aloud of Bernadette Mayer’s poem of that name, there is a part of me that feels as if we are still living through it. As you and I discussed on my back porch a couple weekends ago, we’re in an uncomfortable, unglamorous moment in a number of ways, a space in which it’s difficult to remember the specifics of what came before and equally difficult to predict the end. And we’re also living through actual winter, characterized here in the PNW by dark, short, wet days that succeed one another relentlessly. When Andrew and I tried and failed to go skiing (too many people!) and instead went for a brief hike, we talked about the pandemic and how we are in a dark and midway-feeling period of that as well. It’s impossible to know when we will be done with COVID-era living, but, by the definition I gave above of beginning to forget how it felt before and finding it impossible to imagine the end, it feels like we’re squarely in the middle of pandemic life. On this hike with Andrew through mist and moss and near-deserted trails, I told him that story I texted you and Anneka about recently, the one about remembering sitting in the sun on Bei Hua and Emelio’s deck sometime in April or so of last year, and Bei Hua saying sadly that we might have to curtail our lives for a couple more months—all the way through June. Ha! Soon we will have lived with COVID restrictions for a year. Many things about this era now feel normal, if not great: never eating in restaurants, wearing a mask, performing the elaborate rituals of weather-checking and strategizing in order to hang out outside. But it’s hard to imagine when things might change, and what it will be like. And that statement feels true in many other areas of my life as well.

To me middleness is characterized by a slogging feeling. And I think too one of its dangers, or what I perceive as a danger, is a sort of flattening-out of experience. It feels as if my eye for detail has gotten out of practice over the last year; it glides over the surface of days and scenes, doesn’t snag on anything. I often ask my Hugo House students to tell me something they experienced—highlight, lowlight, small weird thing— in the week since we last met, and I struggle along with them to remember anything beyond the things I take for granted as givens. So much of my last year has been spent in the same few cluttered rooms, on the same few streets of my neighborhood (Fir, Spruce, Alder, 15th through 27th). How much change can I even see anymore? It feels like insofar as the present moment, I am often “spacing out,” a term that feels weirdly right for a mental action that distances one from the excessively near or familiar.

The beauty of Midwinter Day, or one of its beauties, is that it pushes back against that kind of spacing out. It’s a poem-record of the prosaic. And when you read it (that “you” for me is you), it does something that so much of the art I love attempts to do—it illuminates an “unremarkable” experience and its dignity. It maybe even elevates the experience, though not in a way that feels unwarranted; art can make me feel some sense of the actual value every part of a day has, the world’s intrinsic worth.

I’ve been thinking about this, too, during my going-on-six-month stint with Anniversaries, as the mini big-book club makes its way towards the end of Uwe Johnson’s giant novel. One of the things I love the most about it, and which is again a throughline in much of what I love literature-wise, is a kind of carefulness in the sense of being full of care—an intense attentiveness or a devotion to setting down specifics to an extravagant degree. I’ve been wondering a bit about my own ardent love of this aspect of books as I read Anniversaries. Why do I love detail so much? What does it do for me as a reader?

Of course the answer’s not the same for every book! It feels like a different question in Anniversaries than in some of my other detail-laden favorites because so much of Johnson’s novel explores complicity and guilt. Gesine, the main character, is constantly second-guessing her own actions, whether in relation to her work for a bank and a boss at that bank who is “one of the people we were warned about in school. He is Money, hateful and malevolent,” or her reluctance to participate in the protests that periodically arise in New York City in the book. And tons of moral uneasiness also runs under the story she’s telling her daughter Marie about her family and childhood in rural Germany in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s. It feels like everyone in the novel—even Marie, who’s 10!—is both a reluctant participant in systems of power they sense to be awful and ominous, and is insufficiently willing or able to disentangle themselves. All that is to say that, unlike, for instance, some of the Nicholson Baker novels I treasure, Anniversaries does not deploy close noticing “simply” in the service of reveling in the beauty of the world. It’s a pretty dark book in many ways, though that feels like a reductive thing to say—but I guess perhaps another way of saying it is sthat it too has lots of moments of ambivalent middleness, plenty of dark midwinter day feeling. But (or and!) I still exalt in its million moments of brilliant attention, which are inseparable from its care for midwinterness and enmeshment (to use Jenny Offill’s word by way of you):

[The buildings] kept such a proud distance from one another; they left alleyways, Tüschen, between them, not from necessity but from self-respect. They had to have those. The roofs had their backs turned from the market square; like hair partings above faces, they were all supposed to be unique.

…she is sitting surrounded by men at one of the north tables and an empty, dirty sky is behind her, with the shy tops of skyscrapers, silhouetted like cutouts, reaching up into it…

She was conscious that in this minute of standing still outside Mrs. Saatmann’s friendly scattered homey light the wind stood still too, as if curbing its pace.

Now it’s quiet, the asphalt mirror of Riverside Drive shows us the treetops in their close friendship with the sky. A squealing birdcall comes over from the park, like that of an injured young animal. A seagull? Yes, Marie saw it over the tops of our trees—a seagull sawing into the wind, the wind bearing down on our building.

(And these, which I am seeing in retrospect are all wind- or vantage-focused, are just from a 200-page span of the book that I read semi-recently—there is SO much in it, so so many parts I love.)

I am forever exclamation-pointing and starring the margins of my books, as you know, and I think often when I catch my breath at a line there’s some sense of both the unexpected and a match of some sort—I like “match” here because what I am describing feels like both an aligning and an illumination. I’ve heard this described elsewhere, maybe by DFW in an interview, as a “click,” which I am not crazy about because it feels more mechanical than what I’m trying to get at. But my love of the lines above, and zillions of other ones, does contain some sense of “ah, that’s right,” an in-placeness (I want to say “emplacedness”). What I’ve been thinking about a little as of late, though, is that there’s an ease and quickness to that response that does not necessarily register the hard effort of getting those details all the way to me as a reader, getting them down on the page. Bill Carty, who lent me his copy of Midwinter Day for your reading (I traded him a plate of cookies for it in the rain), forwarded me an interesting newsletter last month because the then-newest edition was all about Midwinter Day and Bernadette Mayer. The author, Lucy Diamond Biederman, is a Mayer fan (she’s a poet among many other hats she seems to wear), but the newsletter seems sprung from a line in a recent essay about Mayer (in fact the one you texted me about the other day!) that defends Mayer from what Gillian White, the essay’s author, calls “the criticism made by some in Mayer’s circle that her more conventional ‘personal’ writing makes a romance of domestic life.” Apparently the “criticism” to which White is referring is by none other than your pal Lyn Hejinian! (I feel that she is also my pal just because of how much I love My Life… but, you know, it’s different.) What White and Biederman are alluding to appears in a letter by Hejinian—Biederman says it’s to Rae Armantrout (tweety-bird!), but when I went poking around online it seems like her source, a book by Ann Vickery, actually says that the letter was to Susan Howe. Star-studded poetry gossip no matter what!

The criticism, in Biederman’s words, is essentially that both Mayer’s poem and the story behind its composition—the fact that it was written on the same day it describes—“[present] motherhood and womanhood and writing, and the combination of all three of those things, as easy. Easy for Bernadette, easy and fun and beautiful and silly and charming and lyric, and if it’s like that for Bernadette, why is it so hard for you, you big idiot who’s so bad at being a mother/woman/writer?” Biederman points to the first section of Midwinter Day as an example of this—the section told while dreaming: “This writing/dreaming moment is… to me… where the romance begins: that you could dream and write at the same time, raise children and write at the same time, cook and write, talk and write…”

As I type this out from the notebook where I wrote my draft, there’s a part of me that wants to just say that this is touchy criticism, in the sense that it seems motivated by some sensitivity on Biederman’s part that’s not entirely on the page. I personally don’t get the sense that Midwinter Day as a poem is implying that I’m a “big idiot” for not also writing an epic poem in one day! At the same time, though, reading this newsletter did make me realize something that embarrasses me a little, which is that I hadn’t even thought through Mayer’s story re: the composition of the poem, even after listening to you and others (mostly you!) read Midwinter Day aloud. I feel like I’m a pretty credulous person, and I didn’t even consider whether or not that origin story seemed feasible to me! I just accepted it as cool and true. The net result of reading Biederman’s newsletter definitely isn’t that I now doubt that claim (though Biederman says that Mayer herself said in a lecture that “[n]obody ever believes me when I tell them it was written in one day”). I’m happy to believe in Mayer’s feat! And nothing Biederman says undermines the poem’s power for me, either. But there was something interesting to me—and dare I say helpful?—in thinking about Biederman’s idea that Mayer “hides the hard part.” I guess what I like about this idea is that it seems kind of true of all writing! To return for a moment to the conceit of the middle: all writing takes place in some sort of middle, the space between thinking and sharing that thought in shaped form, and all receipt of that writing takes place in some afterspace in which the middle period, composition, has ended. And even writing that illustrates some sort of difficulty—which I’d argue Midwinter Day does in places, and Anniversaries does too in its very different way—“hides” the struggle of its composition. To quote Biederman one last time: “The process, the perpetual production, to which Midwinter Day claims to be true, is belied by the beauty and coherence of its presentation.” (This makes me think, too, of something I just sent my “Friendship Over Time in Fiction” class as a supplement to our reading of The Waves—I had a huge document of notes on my computer that I took in 2013 as I tried to write an essay on Woolf’s novel, and as research I transcribed a bunch of journal entries from the period during which Woolf was working on The Waves. It’s amazing and heartening to see her saying stuff like, “How am I to begin it? And what is it to be? I feel no great impulse; no fever; only a great pressure of difficulty. Why write it then? Why write at all?” or, “I dont know, I dont know. I feel that I am only accumulating notes for a book—whether I shall ever face the labour of writing it, God Knows.” To me The Waves is a perfect novel, a paragon of “beauty and coherence,” and it’s sort of great to see Woolf flailing around in these entries just as everyone I know who writes does. It’s something I know to be perpetually present, the awful uncertainty of mid-writing, but it still feels affirming to see it set down by someone else, especially if that someone else is Virginia Woolf.)

What I really love, though, is that if Mayer and Johnson and Woolf’s finished texts erase most of the difficulty felt in creating them they still somehow memorialize what it feels like to occupy an interstitial space. I’m reminded of what we you texted me about reading Etel Adnan with Georgia:

I love your description of going from room to room—there’s something so visible and true to me about that metaphor. It reminds me, too, of the feeling I have of transitioning between certain tasks in the house, or getting out of the car, when my arms are full of stuff. I’m trying to carry everything at once and it feels likely that I’ll drop something. I usually feel stressed and uncertain in those moments, fretting about what I might ruin or mess up or just thinking, what has to happen next? But I also have a lot in my hands, and I still have those things later, and they have value: I cook with my groceries, I write in my notebook, I page through the novels I’m teaching.

Another loosely associated idea: maybe a month or so back, Anneka quoted something in conversation that I hadn’t thought of for a while, a line written on a poster I had on my wall in college. The poster was a small and poor-quality print made for an album release by the Kidcrash, the Santa Fe band whose music and members I revered in high school. At the release party Ariel and I had each gotten all four members to sign a poster for us (which makes me wince now, and also laugh—they seemed like celebrities to me, but they were actually just boys who were barely twenty!). Alex, the lead singer and guitarist, wrote on my poster: “One day this will be a fun memory.” At the time I thought this was both aloof and genius, which definitely fit the narrative I had created in my mind. Now it seems more flip than anything, but, despite the fact that Alex probably put no thought at all into it, there’s also something about the sentence that sticks easily in my mind, both sonically and as a kind of adage. It’s been returning to me a lot since Anneka said it, and what it seems to say is that any given moment of middleness will someday not be the middle—it’ll be something that happened before. This is extremely obvious but also feels helpful to me! Do I think that this era of our lives, COVID-wise and otherwise, will someday be a fun memory? Probably not a fun one. But it will be a memory or, to use Jinny’s word from The Waves, a “hoard” of them. And some of the difficulty will be replaced with interest. But I guess I wonder too if this particular era of middleness will be especially good at reminding us, once it morphs into memory, of those moments of being between rooms, wondering if you can hold what you carry.

If I have faith that I can weather those kinds of moments, even if I drop what I’m holding, it’s because I believe I’ll have good company of some kind, both in the moment and in my remembering. So many of my now-past middle moments, other bad midwinters, are shared with you, in my mind and in our conversations and on paper. I think of our infamous “fight” outside Salt & Straw in Portland, or of talking to you and Bill on the fourth floor of the Bard library before going to have a hard conversation in the campus graveyard, or of sitting in the car outside the Santa Fe co-op with you and Anneka, crying as sun arrowed in through the windows. And I also think about all the written records you and I have sent each other, thus both keeping and giving away these middles: your typed notes from Bard journals (“Friday December 11 2009. Wake up by Liza, we draw rebuses for Mikee: ‘We bialy leaf in you,’ ‘Like a rolling scone,’ ‘cross-aunt(ant)’ —bakery, he loves them, gives us madeleine—we go to school—Proust, madeleine—"), our project of sending each other postcards every day for a month, and our two “public” collaborative epistolary essay projects, the first the one for my poetry workshop at UMass where I accidentally spent $80 at the copy shop making facsimiles of our letters, the second the one for Edie’s anthology, which was three times longer than she’d asked for and which got rejected. These middles, your middles which I can pull out of a drawer or up from my email inbox and look at now, are my middles too, and I feel love for them:

My letter to you today is muddy and unintentionally springlike in its lack of clarity. Like I said, I feel I just keep circling, alighting almost, re-circling again, like the birds outside your windows that I can’t hear but can imagine hearing, almost, though I don’t know birds like you do and so the sounds I think I hear are invented by me or by countless other unidentified bird-times, bird-things, bird-sounds from the Hudson Valley or Santa Fe or among the hedges of a period piece I watched while preparing an envelope for a friend. I feel I’m getting closer but I might just be seeing this spring with the dim casts of all our past springs, too—and maybe the sum of all that is what astonishes.

(That’s you on April 24, 2017, referring in your last phrase both to My Life and to that Denise Levertov poem we both love, which I sent part of to you in this same collaboration, a poem also written from and about a middle time, I think:

Try to remember it is always this way.

You live

this April's pain

now,

you will come

to other Aprils,

each will astonish you.)

So many of the times I just referenced were difficult in various ways, and some of that difficulty has dissipated, and some of it has remained. But what I have been thinking about as I work on this letter is just how much particularity can mean after the fact, even if it’s the particulars of being miserable, and how much particularity is, for me, made sharper by the presence of others, whether a friend or the voice of a book. I think of The Waves again, and the passage that I told you about sending my students to make the case for the book’s portrayal of friendship:

"Something now leaves me; something goes from me to meet that figure who is coming, and assures me that I know him before I see who it is. How curiously one is changed by the addition, even at a distance, of a friend. How useful an office one's friends perform when they recall us. Yet how painful to be recalled, to be mitigated, to have one's self adulterated, mixed up, become part of another. As he approaches I become not myself but Neville mixed with somebody—with whom? —with Bernard? Yes, it is Bernard, and it is to Bernard that I will put the question. Who am I?"

I don’t think I would know the ever-shifting answer to that question (which might as well be the questions “What is around me? What do I perceive?”) without you, and I don’t think I could have made it through so many middles without being recalled, adulterated, and expanded by our friendship. Thanks for always making it a part of your life, too, and for puzzling over difficulty with me always. I love you!

love from

LJB

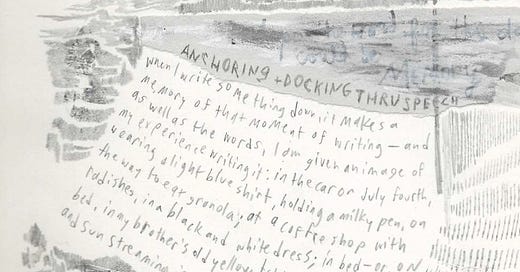

(Art in the first image is by Molly from her Winter Journal series. The epic pic above was taken by Andrew. Hi everyone! Miss you all!)